Making choices - William Ludwig Lutgens at PLUS-ONE Gallery

Gallery Viewer Magazine (link)

28 october 2024, written by Indra Devriendt

Do we live in a degenerate society? It seems as if we’re all drawn towards flaunting ‘more’ and ‘better’. There’s a danger that performance and stress will take precedence. But thankfully, we largely make our own choices and are responsible for our own well-being.

We see a spectacle of puppets. They’re acting like zombies, creating surreal scenes that are both unsettling and pitiful. Stress, fatigue and/or ignorance can sometimes prevent us from seeing other options. At PLUS-ONE Gallery, we see the first film by William Ludwig Lutgens. “My subjects live in a performance-driven society,” he explains. “These figures are so exhausted that they are no longer able to function, yet they’re unaware of this, so they just keep going. They end up in a zombie-like state, similar to depression or burnout. I consider these the epidemics of our time, fuelled by overstimulation in our society.”

His current exhibition, titled Fantasy Supplement, borrows its name from Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek. “He uses this concept to highlight the use of fantasy as a defence mechanism,” says Lutgens. “We use fantasy to avoid confronting things like trauma. We convince ourselves of things to justify our choices, believing that we must perform and that stress is normal.”

In the film, we hear a strange voice-over. “I used the voice of an old British woman, slowed with AI and layered with effects,” Lutgens explains. “I came up with a number of ideas and the text was written by Cecilia Bien, a researcher and writer from New York. We met earlier this year during my residency in Paris. The texts explain the concept of jouissance, a complex term in Lacanian psychoanalysis that means finding pleasure in pain. It’s uniquely human to inflict suffering on ourselves. We explain jouissance in the film through the concept of the abject, as defined by Julia Kristeva—a word for something that disgusts you.” The visuals are rich, often distracting us from the text. Lutgens filmed at the former Sint-Trudo Abbey in Sint-Truiden. The video Joy Sauce, a playful spin on jouissance, is part of an installation. It’s displayed on a laptop in a drawn room portraying the chaos of daily life. Paper-mâché-covered chairs invite us to observe the scene. Lutgens feels that two-dimensional works have their limits and aims to create more video installations in the future.

Lutgens grew up in a family where work, achievement and earning money were matter of course. “As a teenager, I rebelled against this neoliberal mindset, but it shaped me all the same.” He graduated from HISK in 2017 and in 2018, had his first solo exhibition at PLUS-ONE Gallery, marking a strong start to his artistic career. A busy bee, he has been publishing a newspaper, Het Geïllustreerd Blad, since 2016 and in 2022, founded Red Herring Salon to promote exhibitions and foster artist networks. “I thought I could handle everything. I was getting good at what I did, so I filled my time with more work.” Last year, he ended up with a burnout. His recovery made him realise the need to slow down. He now focuses solely on his art. His recent drawings show a clear evolution in both form and content. “Whereas I used to add as much as possible, I now embrace simplicity.”

Lutgens primarily showcases paintings, though he’s a draughtsman at heart, with subtle hints pointing to his love for the medium. His canvases are framed with paper-mâché borders and he creates line drawings on transparently primed canvases.

“Someone told me it has a calligraphic feel, which I like. I first spray the black lines, then add shadows with an oil stick, followed by colours in chalk ink. I try to keep the colours consistent, but each piece is always a variation.”

This series of drawings forms a cohesive body of work through recurring techniques, colours, characters and imagery, which invite connections, though there’s no clear storyline. Here, too, we feel the tension between performance and speed, doing nothing and slowing down. Lutgens fills his drawings with a figure wearing a tie, occasionally with hooves or horns, and a sock puppet. “I wanted a hybrid between a performer and a drifter. The tie represents performance, while the goat is inspired by Pan, who to me, feels like an ancient drifter. He wandered the fields, playing the flute and causing mischief. The sock puppet represents self-deception and is inspired by Liegebeest, a 1980s Belgian series with a hand puppet that lies to everyone. We’re driven by performance, but this puppet deceives us, keeping us from seeing reality.”

The half-goat figure with a tie and the sock puppet perform household tasks, work on a laptop or speak into a microphone. “During my residency in Paris, I had no goal and did whatever I felt like, which was often nothing—something that is not acceptable in today’s society. I feel guilty if I postpone work for a day, though I shouldn’t. Sometimes, I spent an entire day doing household tasks, eating and sleeping, but I felt like I hadn’t accomplished anything. The laptop symbolises our constant connectivity. On social media, even making your bed can become a performance to display your productivity. We’re so absorbed in the digital world, but are we aware of its effect on our mental well-being?” The microphones also reference performing, looking good and wanting to be on stage.

What do we spend our time on? What gives us fulfilment and supports our mental well-being? These choices are ours to make. Thankfully, we can make changes when we are no longer able to handle pressure and expectations. One moment, we may want to achieve and reach goals and the next, we may release our inner drifter and enjoy doing nothing.

Happy To Hear You’re Doing Fine - William Ludwig Lutgens

04/03 - 30/04 /2023

Expositieruimte 38CC, Delft, The Netherlands

To be born at all is to be situated in a network of relations with other people, and furthermore to find oneself forcibly inserted into linguistic categories that might seem natural and inevitable but are socially constructed and rigorously policed. We’re all stuck in our bodies, meaning stuck inside a grid of conflicting ideas about what those bodies mean, what they’re capable of and what they’re allowed or forbidden to do. We’re not just individuals, hungry and mortal, but also representative types, subject to expectations, demands, prohibitions and punishments that vary enormously according to the kind of body we find ourselves inhabiting.

(Olivia Laing, Everybody: A Book about Freedom)

In the first room, they sit on chairs, five of them, as if in a waiting room, waiting to hear their name called out loud. Or to be named in the first place. Their work-appropriate clothing is soaked in layers of oil paint, forming a membrane of sticky, painterly substance.

In the room that follows, they hang on walls among paintings of various sizes, like surrogates for their two-dimensional counterparts. Yellow, the colour of madness, returns in each one of their eyes.

The eye registers a human shape in the peripheral field, and almost by reflex, the head moves laterally to allow the figure to enter the centre of the gaze. Essentially, we do function as mirrors for each other, don’t we? Gazing at bodies with projection beams, speaking at them with the words addressed to one’s self. The puppet bodies are waiting to be endowed with meaning, offering themselves as therapeutic tools in hopes of becoming, like Pinocchio, a ‘real boy’ along the way.

A white-walled exhibition space is designed to appear neutral, stripping the displayed object of context. Perhaps it echoes a pursuit of purity of experience, although a commercial function is equally implicit. The white space is never neutral, the experience it induces is bound to a particular tradition and motivation. The puppets are hung as paintings to be seen as paintings on a white wall, to be subjected to the conditions and assumptions the white wall offers, inclusive of the implied potential to function as objects of economic exchange. In this regard, the artist winks at the notion of zombie figuration – a style defined specifically in relation to the art market trends in recent years. William Ludwig Lutgens creates, quite literally, figurative painting zombies, simultaneously embracing and challenging the notion that has been used as a critique of the stagnant status quo in painting.

Happy to hear you’re doing fine is a phrase that the artist has borrowed from a film by Roy Andersson, whose characters repeat it in several scenes during conversations over the phone. Asides from the dark humour, there is a sense of individual isolation in those scenes, as well as a particular relationship to language, which corresponds to that of the characters in the works of William Ludwig Lutgens. Moving between drawing, painting, and sculpture, the work of Lutgens is consistently in internal dissonance with the tradition and the conditions it exists in, gaining a symptom-like quality through the implicit return of the repressed.

William Ludwig Lutgens, 'My mind is the mind of a fish'

03.09—09.10.2022

PLUS-ONE GALLERY (NEW SOUTH)

Written by Anna Laganovska, 2022

My mind is the mind of a fish is a solo exhibition by William Ludwig Lutgens, presenting a selection of the artist’s most recent drawings and paintings. The works of Lutgens often emerge as a condensation of the streams of information that flow through his mind, from news programmes to overheard chatter. Snippets of realities, fantasies and fixations are given form on paper, wood, canvas and aluminum. Lutgens uses various painting techniques in an experimental manner, freely altering between watercolor, oil and acrylic paints. In his signature illustrative style, William Ludwig Lutgens creates works that reflect upon our social and political realities, as well as human behaviors, urges and lusts.

“My mind is the mind of a fish” are words Lutgens has borrowed from the American artist Paul Thek, written in a letter to Ann Wilson in 1969. In this letter, incoherent thoughts jump back and forth in a scattered sequence of sentences, hinting at madness or intoxication. The artist’s self- diagnosis is made in reference to the mind of a goldfish – only capable of holding on to a thought for five seconds according to a popular but mistaken belief. For Thek, though, there is comfort in the expressions of madness, in the incoherence of thought. There is an urge to transgress the objective reality, and an appreciation of the irrational as an escape or a path towards an insight of a special kind, which Thek considered the essence of art, incidentally.

My mind is the mind of a fish, like the mind of Lutgens, born in March, the Latin Piscis, plural Pisces, the constellation of two fishes entwined, and the zodiac sign, mutable water. One fish is directed towards the east, and the other towards the west: towards the spiritual, and towards the earthly realms. This constitutes the primal conflict in the Pisces who is all too aware of both directions, but slightly more comfortable in the heavenly realm than in the physical one. The ultimate objective is to have both fish healthy, energetic, and in touch with their process, swimming merrily along. But the mutable quality in the Pisces means that it has already had enough and it needs change – it is the gloom at the end of winter, dark and cold for too long, bearing the promise of spring, but not quite there yet, waiting frustrated.

My mind is the mind of a fish, and there are these two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says: “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes: “What the hell is water?” This was an anecdote that David Foster Wallace began his famous commencement speech with, adding that the point of it is that the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about. The platitudes of everyday realities find their way into the work of William Ludwig Lutgens absurdly heightened, soaked under layers of bodily fluids, with a naked butt and eating potatoes. He is the other young fish trying to dodge the question about water with a silly joke, then laughing nervously, and staring off into the distance.

My mind is the mind of a fish, submerged in water, fluid, flowy, wavering, and above all mysterious, hence the most common symbol of the unconscious. For fishy creatures that we are, descending from water in an evolutionary sense, the unease surrounding this visceral matter is somewhat bizarre. There are old tales of Sirens, Nixies, or Rusalkas, singing songs so sweet and seductive one had to lose oneself, and tragically, in the waters upon hearing them. Thus the sense of danger, but perhaps the tales tell more about the relationship to the unconscious realm than the threats of it in itself. The piscis swims in the waters, and yes, he gets lost and seduced by the streams and the flows, but isn’t that the whole point of – I don’t know – his life?

On the work of William Ludwig Lutgens

written by Céline Mathieu, 2022

It is not actually a painting but it still kind of is one. It is a painful historical marker with an open face, weighed down in the middle like a critical remark. Be it in two or three dimensions, William Ludgwig Lutgens’ imagery looks outward, candidly welding value and composure.

It is so visceral, Belgian painterly, and historically charged. It is going towards something while moving away from it: a depiction of the uncomfortable recognition of entangled responsibilities. Titles sound like ‘An ocean of currency/water for the rich’ or ‘Capitalist rats making a stew from golden coins’. We see carousels and people going on in circles, remembering the dizzying reality of how things are composed on a larger scale. Things click on and off: shoulder whispering angels; soil moving workers; decapitation after decapitation—so many loose heads in William’s work.

And smaller, closer to home, the work holds references to being an artist and to bodily awareness on an intestinal level. I imagine the slightly nervous presence in/of the artist and the wobbly line of his hand, the openness of the page, his existential wafts and thoughts on protest culture. His pedestals are built like Jenga, and a chair for a character suddenly became too small for a body that weighed down by societal hooks. Every scrap of wood, cloth or paper used, holds traces of a studio environment. His crossing histories are smiling but confused. A drunk-night-vision Ensor meets Goya meets BBC meets Latin classes meets graffiti.

In the same grabbing gesture, I gather three books from my shelf, mostly going off on their titles, while thinking of Lutgens’ work. ‘How to live together’, ‘The Shaking Woman’, and ‘Work, Work, Work’.

In the book ‘How to live together’, a situation is sequentially sketched as follows: (a) a loud booming voice, (b) unembarrassed discussion of all sorts of subjects, (c) lolls over two seats, (d) takes her shoes off, (e) eats an orange, (f) cuts in on my conversation with my travelling companion. The passage serves to explain what it means to “hold forth”. The sequential reading of this situation, accumulating familiarity and frankness, reminds me of looking at Lutgens’ characters. In my mind's eye I see these characters – and I’m trying to find the most straightforward term for fucking? – I see them fucking, so frantically, that you wonder what character’s dissociated genitals you’re now looking at.

The images of William Ludwig Lutgens are blunt. There is the deceiving simplicity of candour, but really it is all made of lists, signs and notations. Lutgens’ characters swim in flooded Wallonia. The eye reads and adds to the open lined characters in each drawn situation, the way you read a comic. Dots of colour, dirt and anything that reminds you of crusted paint on a cold coffee mug, smear the artist’s studio onto the work. In short, he holds forth, with his coded figures.

William mentions the Global News, capitalism, Freud and Fromm, touching on them, pressing briefly, and brushing them away, avoidant to make claims. The unconscious was often unaware of his own motives. It still strikes me as strange that the case histories depicted would be read like short stories. There are events and we weave them into a narrative that makes some kind of sense.[i] I was thinking of William and read about grief and melancholia. I tried to imagine the nagging biting rat he tries to shake off, while feeding his studio practice with BBC fragments, fueling gallery anxiety and classic old school artist pressure with coffee. Is it grief I wondered, “for a person grieving the outside world turns grey and meaningless. In melancholia however (…) there is a blur of betweenness, or partial possession by a beloved other that is ambivalent, complex, and heavily weighed with emotions he can’t really articulate.”[ii] It must be something like that.

In the preface of ‘How to live together’, Kate Briggs writes: “Books of all kinds, traditions, and historical periods are variously pored over or merely dipped into; unlikely volumes are set alongside and made to walk in step with one another, obliging us to rethink what we mean when we speak of contemporaneity.”[iii]

Then in the other book I chose for its title, Work Work Work, I find a piece by Hito Steyerl that makes me smile, hinging on thoughts of all (encompassing art) lives and the simple occupation of it. She writes: “Art has not only invaded life but occupies it. This doesn’t mean that it’s omnipresent; it just means that it has established a complex topology of overbearing presence combined with gaping absence— both of which impact our daily lives. (...)

Wondered how you got caught up in the endless production of productivity and the subjection of subjectivity? Do you wake up feeling like a multiple?”[iv]

This ties back nicely to the exhibition at De Garage in Mechelen, which I tried to describe below.

William Ludwig Lutgens at De Garage in Mechelen

For his exhibition ‘The bigger the short, the sweeter the bottom’, second-skin suits are stuffed and dressed up as higher middle-class office workers. These “dolls” line in the space in protest or shame: forming a human wall, held in place in a pillory, or peacefully demonstrating on a truck blasting slogans. As though they were protesting, the dolls hold the middle between being an actual body and a tool for representation. Subtle but flagrant like a dusty scent, his work rubs together different histories: painterly Belgicisms, comics, and politics. In one of his drawings in the exhibition, figures swim in flooded Wallonia; the characters seem animated, under the influence and disconnected at once.

Thoughts on freedom and repression run through the show. Human commodities of profiling, From the way we learn skills to the way we dress, from the partner we choose, to the car we own: the creation of our identity becomes leverage. Like an expensive loafer or a steak-stuffed businessman, we might ask what confining structures do we give shape to for them to shape us in return?

News quotes find their way into titles of works, some of which are made on handmade paper. By recycling old paper, he makes thick pulp and processes it into new sheets that dry on a line like laundry: chewed world news. The paper, undone but still remembering its content, looks like concrete walls in the way it is mounted on canvas in Ludwig’s show. Potatoes, a borrowed Belgicism, fill the exhibition floor. Their stuffy quality nicely aligns with the starchy civilian characters in the space. In a mesh, different sources and types of information and dreams are processed – only seemingly random traces are left. Lutgens' paper processing room nicely alludes to the covering and undressing of uncensored pulp. Vieze mannekes, as his neighbour used to call his childhood drawings, still rule his universe. The men bathing in a flood speak to the puffed people protesting in the flesh.

Black A, white E, red I, green U, blue O— vowels

Some day I will open your silent pregnancies:

A, black balt, hairy with bursting flies,

Bumbling and buzzing over stinking cruelties.

This is a poem by Arthur Rimbaud titled Vowels. I found it in Shaking Woman, by Siri Hustvedt and was a bit bummed this too was another white dead man to mention. For me it was the playful, seemingly careless way of throwing up vowels while describing the underbelly of dirt and knotted complexity, that made me want to add this poem. Not for it’s poetic linguistics but for the gestural sway and the unwell underbelly; what my friend Natasja Maseboone nicely pointed out as an“Urbanus” feeling, excuse the Belgian reference. But then we looked up Arthur Rimbaud, and William sent me an old picture of the old dead historical person we had to admit not having read much from. William plainly wrote“grappig mannetje”; funny little fellow, and the carousel was on again.

[i] Siri Hustvedt, ‘The Shaking Woman or A History of my Nerves’, p 126

[ii] Siri Hustvedt, ‘The Shaking Woman or A History of my Nerves’, p 126

[iii] Kate Briggs in the preface of ‘How to live together’ by Roland Barthes

[iv] Hito Steyerl, ‘Art as Occupation’ in ‘Work Work Work, A Reader On Art And Labour’ p 52

William Ludwig Lutgens’ That Clinking, Clanking, Clunking

06.03.2021 / 15.04.2021 Bruthaus Gallery

By Anna Laganovska

In the exhibition That clinking, clanking, clunking William Ludwig Lutgens in a

characteristically playful manner interprets aspects of life in financialized capitalism.

Playing with the idea of chair dance, the artist creates a world of absurd, associatively prompted characters entangled in the dynamics of competition. Consisting of works in sculpture, painting and drawing, as well as audio, the exhibition illuminates artist’s multidisciplinary way of working and urge for technical and material experimentation.

William Ludwig Lutgens was invited to create the exhibition at Bruthaus gallery in Waregem as the laureate of the Gaver Prize 2020.

Essay by Anna Laganovska, published in ‘HGB Nr.7 - That Clinking Clanking Clunking’,32 pages, edition of 115.

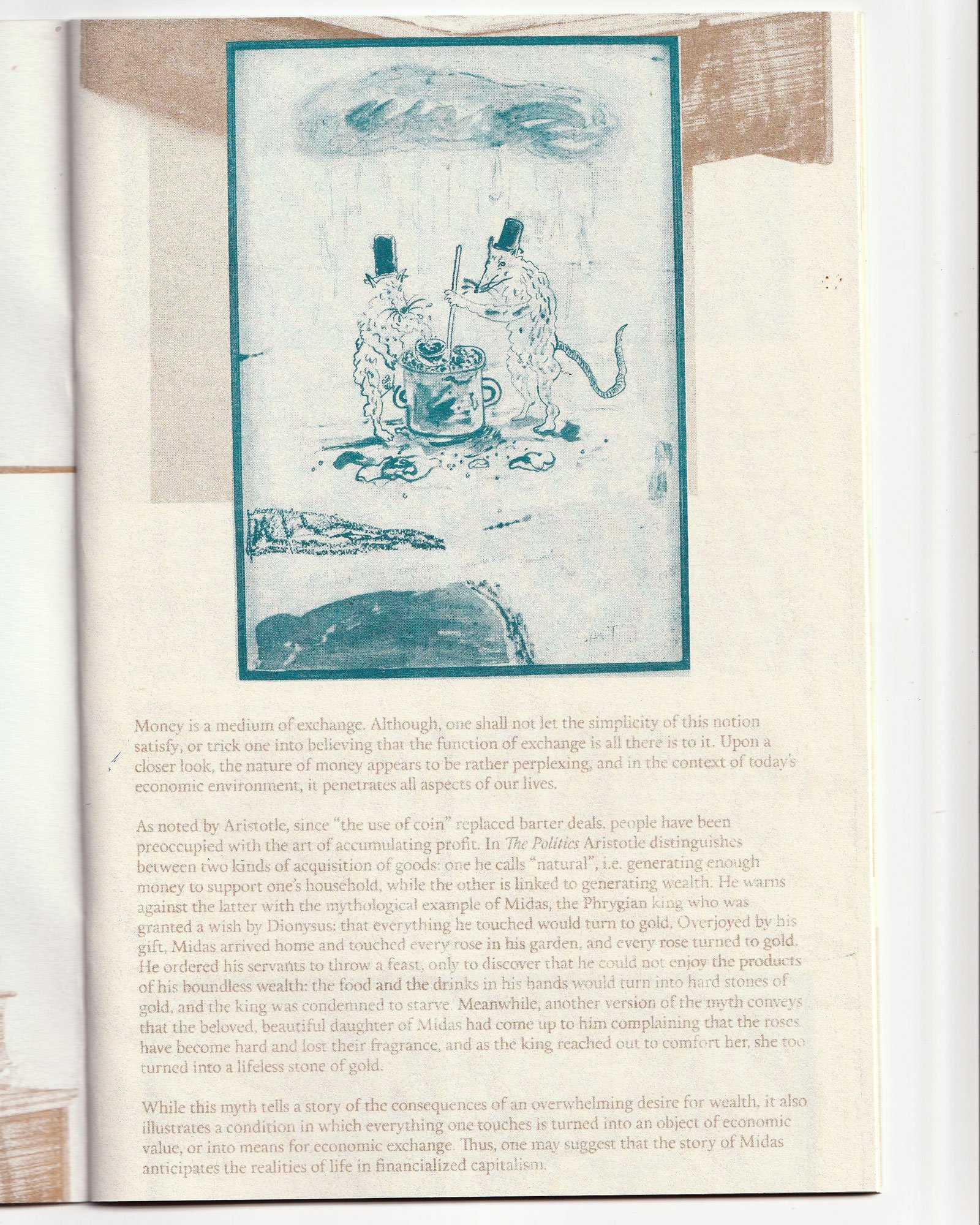

Money is a medium of exchange. Although, one shall not let the simplicity of this notion satisfy, or trick one into believing that the function of exchange is all there is to it. Upon a closer look, the nature of money appears to be rather perplexing, and in the context of today’s economic environment, it penetrates all aspects of our lives.

As noted by Aristotle, since “the use of coin” replaced barter deals, people have been preoccupied with the art of accumulating profit. In The Politics Aristotle distinguishes between two kinds of acquisition of goods: one he calls “natural”, i.e. generating enough money to support one’s household, while the other is linked to generating wealth. He warns against the latter with the mythological example of Midas, the Phrygian king who was granted a wish by Dionysus: that everything he touched would turn to gold. Overjoyed by his gift, Midas arrived home and touched every rose in his garden, and every rose turned to gold. He ordered his servants to throw a feast, only to discover that he could not enjoy the products of his boundless wealth: the food and the drinks in his hands would turn into hard stones of gold, and the king was condemned to starve. Meanwhile, another version of the myth conveys that the beloved, beautiful daughter of Midas had come up to him complaining that the roses have become hard and lost their fragrance, and as the king reached out to comfort her, she too turned into a lifeless stone of gold.

While this myth tells a story of the consequences of an overwhelming desire for wealth, it also illustrates a condition in which everything one touches is turned into an object of economic value, or into means for economic exchange. Thus, one may suggest that the story of Midas anticipates the realities of life in financialized capitalism.

We’re building up now to the finals of the chair dance. Now, on the field, William Ludwig Lutgens, a young Belgian champ, at the chair number seven among previous winners – Aristotle, King Midas, Herbert Spencer, John von Neumann, Bill Gates, J. K. Rowling and DJ Tiësto himself who appears once again here, he was the 2004 champion. What a line-up we have, the chair dance final.

On your marks. The crowd is thrilled. Set - [music plays] (dj_tiesto_adagio_for_strings.mp3)

Financialization is a periodizing concept that refers to the ongoing developments in the financial sector, which began in the 1970s and led to an increased power of the financial sector in politics, economy, social life and culture. This increased importance of finance implies that its ideas, values, processes, metaphors and narratives have migrated beyond the bounds of the financial sector and are transforming other areas of our lives. Furthermore, financialization

coincides with a shift to cognitive-cultural capitalism, which refers to immaterial assets being at the centre of accumulation of capital, as well as to the shift towards new, often precarious forms of employment, well exemplified by what is known as “gig economy”. From the perspective of cultural analysis, these economic developments have had a substantial impact on the way we conduct our lives. As argued by Max Haiven, “these transformations have required the cultivation of a new wardrobe of subjectivities that encourage each of us to address ourselves as competitive entrepreneurs who see all aspects of our lives as a portfolio of assets to be leveraged for future payback, from friendships to hobbies to physical attractiveness to educational attainment.” Not only is competition a defining element of our lives, but we are urged to be and valued for being competitive.

Well, off we go, eight players, seven chairs. We’re witnessing the best of the best here, the tension is in the air as the players exchange looks, finishing the first lap around the chair arrangement. Gates, what a legend, he gives a sly smile to Lutgens who responds with a deadpan stare. The young Belgian cannot be intimidated. Tiësto is looking confident today, as he two-steps to his own beat. Fist in the air, the audience cheers. Spencer and Neumann seem to keep the pace down, they might be elderly, but don’t be fooled, these men are ruthless. Rowling charms the audience with an elegant twirl, moving between Aristotle and Midas, what a company we have here today, and, the referee –

[music stops]

Players shoot to the seats, oh, Spencer is out.

There is a long history of figuratively considering or modelling economic activities as games, particularly in relation to game theory, the influence of which in economic philosophy cannot be understated.

In the exhibition That clinking, clanking, clunking William Ludwig Lutgens interprets a state of competition through the allegory of chair dance – a popular party game, in which the players are circling around a set of chairs to the sound of music. The number of chairs is fewer than the number of players. When the music stops abruptly, everyone has to find a chair to sit on. The players failing to achieve it are eliminated, and the game is continued until there is one winner left. The chair dance is a typical example of a zero-sum game, which is at the basis of game theory. A zero-sum game is a situation in which the common goal cannot be shared, and one player’s success necessitates the loss of others.

Considering the capitalist competition, one has to think of the phrase “survival of the fittest” and the ways it has been used to justify and promote competitive relational models as “natural”. Even though this phrase is rooted in the Darwinian evolutionary theory, it does not

originate from the writings of an evolutionary theorist. Indeed, the person to coin it was the 19th century British philosopher Herbert Spencer, who, after reading Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, suggested that the principles of natural selection may extend into the realms of sociology and ethics. Over time, however, the “survival of the fittest” principle has become so worn-out in popular culture, that it has developed certain connotations that could be seen as nothing but misconceptions.

For instance, certain confusion may stem from a lack of emphasis on the fact that competition is only one of many relational models in nature, and not even necessarily the most successful one. Instead, it could even be argued that the real evolutionary success stories are to be found among species of cooperative kind. And, to bring this idea even further, the fallacy of emphasising inter-species competition over inter-species cooperation could be framed as a contributory factor to the ongoing 6th mass extinction, essentially, a conflict between the competing human interests and the interests of other species. Now, how is it that we are so widely convinced that we should structure our lives on the basis of competition, rather than cooperation? One may easily draw a link here between the dichotomy of competition versus cooperation and the two ends of the political spectrum. Although, even if these relational paradigms fit so perfectly with the political agendas of the right and the left, one shall avoid the temptation of appealing to one “natural”, superior principle of order when arguing for one of the approaches. As pluralistic as the natural world is, as pluralistic shall we humans be.

[music plays]

Round three, here we go, round three chair dance finals. King Midas has so far slid through the game leaving gold chairs one after the other behind, he squeezed Lutgens out of his seat as the Belgian supporters broke their own chairs in outrage, two men escorted from the stadium. It’s down to six, down to six players. Referee calls for silence as the heartbeats quicken. What an iconic game. The pace goes up, this is going to be a very, very close run, we’ve got Tiësto, we’ve got Gates, Rowling, Midas and Aristotle still in the game.

But most times there does not seem to be much choice. The economic game is a zero-sum situation one can’t go avoid. In fact, most of the time, as in chair dance, it is random: one’s chances depend on their position, on their surrounding players... And, to say it softly, it is just not nice to live in such a competitive environment. As many left theorists have argued, there are obvious links between the radical competitive individualism we live by and the overall decline in mental health. “In the entrepreneurial fantasy society, the delusion is fostered that anyone can be Alan Sugar or Bill Gates, never mind that the actual likelihood of this occurring has diminished since the 1970s (..),” notes Oliver James, “The Selfish Capitalist toxins that are most poisonous to well-being are the systematic encouragement of the ideas that material affluence is the key to fulfilment, that only the affluent are winners and that access to the top is open to

anyone willing to work hard enough, regardless of their familial, ethnic or social background – if you do not succeed, there is only one person to blame.” Although, this idea that one succeeds or fails on their own is simply not true: neither amongst individuals, nor states and societies.

It does seem almost tasteless to keep underscoring the deception and toxicity of the merit- based narrative, which frankly leaves most of us in the category of being “average” and “incapable to compete on this level”, both perceivable forms of failure. That is, until one faces a situation which proves how, apparently, unobvious it is to conclude that: a class in cultural economy, in which the professor singles out the cases of J.K. Rowling and Dj Tiësto as the only lucrative, thus, worthwhile forms of artistic practice. These cases, being examples of a product that can be created with low costs and endlessly reproduced, are then contrasted with the highly cost-ineffective and non-reproducible practices of dance and theatre. Meanwhile, the arguments that Rowling was depressed and living on social welfare while writing Harry Potter, but Dj Tiësto is not exactly the highest achievement in music, just don’t hit the spot.

[music plays]

Down to four, we are down to four players in the chair dance finals. Tiësto, Midas, Gates and

Rowling, what an astonishing final group, four countries, two historical epochs, epic. Rowling gives a little shoulder dance, yes she does, she is putting up a good show today, but there is a lot of debate as to whether she will be able to remain the sort of standard till the end, she came second last season which was a very, very fine run, and it shows that she’s world class, but will she deliver. Gates moves closer to the chairs, we’ve seen this move from him before, bringing the whole group closer together as the race develops here with three rounds to go.

Since the Cognitive Revolution, marked by the developments in human communication which allowed for common comprehensions of things that do not physically exist, such as myths, gods and religions, there has been no natural way of human life. Instead, the history has been made up of cultural choices. Seen as cultural choices, our ways of being, ways of conducting relationships to the world around us, are imagined orders. Although the imaginaries we live by often seem conspicuously natural, they can – and eventually will – be replaced.

The story of Midas ends with the king turning to Dionysus to ask for his wish to be returned after realizing that his blessing was actually a curse. Midas was instructed to wash his hands in the river Pactolus, historically known as an important source of gold and electrum. Asides that, King Midas was also known for having donkey ears.

[music stops]

Here comes King Midas, King Midas storming to the chair! Rowling trips on her wide-cut trousers, and he takes it again! King Midas! Brilliant, brilliant, brilliant! King Midas the Phrygian is the winner of the chair dance. A superb demonstration of chair dancing. What a performance that was. Rowling attacked early, but King Midas got into his game, really, it was an unbelievable run. He is heading to his celebration, could not be beaten, he promised and he delivered. The game is finished, and in the half way King Midas emerged from the pack and powered his way to the chair in the most empathic way. He is the winner. He has had his problems over the last couple of seasons, but if we ever doubted him, well, that now goes to the history books, the Phrygian prevailed. In past, of course, we had, Bill Gates, we had Tiësto, we had Lutgens, but this time we’ve got King Midas, transcending the world of the chair dance once again. That. Was. Incredible. And this crowd here have seen the demonstration by the man they’ve seen on posters all around the city, all around the television, they’ve seen him in person, they’ve seen him deliver, oh-my-goodness, didn’t he deliver. We’re privileged to see this man in action. It is a privilege, it was keenly anticipated, he lived up to his rich promise. It’s a moment of history, chair dance history we’re witnessing here. The donkey-eared men couldn’t chair dance, they said, well, that’s not true. Look at this celebration.

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Fool

On William Ludwig Lutgens’ A Comedy of Humours, 2020

By Michaël Van Remoortere

We live in hysterical times. Even when the world came to a screeching halt and the apocalypse did not announce itself with “lightning and thunder” or “archangel trumpets”, but through the silence of empty streets and live-streamed funerals, we were flooded with interpretations, opinions, soundbites, convoluted powerpoints and, as if things were not bad enough already, a newly invigorated moralism disguised in the pret à porter rags of Art. It was supposed to be a time of introspection but when the smog had cleared, we discovered there was no revolution in the air and yet we called our despair hope to mask our powerlessness. But amidst this turmoil of timeliness, we seemed to have forgotten this most untimely of all human endeavors; laughter.

The axiom of history repeating itself has reached the status of an obsolete and meaningless cliché. No longer an imperative of self-consciousness and knowledge, it has become an easy excuse for immobility. Nevertheless if one looks closely, the possibility of reading history anew has not vanished. Yet in order to do this one needs distance, a distance that lends itself most willingly to a specific insightfulness lying at the center of that overlooked humanistic method of research; (the) comedy. Whose definition might be the gap between ideals and reality. As such differing with tragedy only because of its inclination towards action and resilience. The distant view that allows us to broaden our scope and understanding of la comédie humaine, which only recently got called history, is what is at stake in the paintings of William Ludwig Lutgens’ A Comedy of Humours.

The beautiful surfaces of these canvasses hide a deeper, unnerving probe into the historical theories that underlie and overshadow our daily existence. The narratives that are simultaneously constructed and halted in the anecdotal scenes we are presented with, still exhibit the contemporariness of the direct observation, but have benefitted from a deep and thorough engagement with the history of art that nevertheless does not burden the image with

heavy-handedness. The references are sprinkled through the series with the same generous levity and joie de vivre Lutgens conveys through his vivid approach to color and swift application of paint.

At first glance we are seduced by the misleading intuition these paintings were made quickly and seemingly off the cuff. Only on closer inspection the images reveal the density of their layers of meaning and the rigorous compositional research of which they are the result. As an artist firmly grounded in this time we share, a “time out of joint”, Lutgens knows how to move with agility (and I’m doing my best not to use the word grace) between both the remnants of history at large and the debris of present-day urban (and digital) everyday life. But it is his vision that reassembles all these signifiers into new and unexpected meaningful constellations that seduce us beyond any defense. So they can floor us unexpectedly.

Because this artist is a con man. As much as he likes us to believe him to be no more than a very skilled trickster, Lutgens has something to say, even though it might not be really clear to us what that might be. His message is never a direct one. The themes his paintings address implicitly - because his ideal audience is of the thinking kind - are not those one should be laughing at. Paradoxically however the comedy of his anecdotal approach is an invitation for us to meet the matters at hand halfway, far from any preconceived idea about, to only name a few, the post-colonial treatment of the relationship between Congo and Belgium, Black Lives Matters, the pandemic and its quarantine, the superfluous art world of the moment and all the people who profit from these movements and events.

Knowing that he cannot raise these matters without in some way incriminating himself, the artist paints a portrait of himself as young fool. Either inside the frame or as the limitations of the gaze that beholds the unfolding of the events. A caricature of the Western man, not unlike his Belgian compatriot Tintin and the fellow travelers of more “innocent” times, the big-nosed character hopping in and out of these observations never fails to be flabbergasted by the situation in which he finds himself. The story of how he went to Congo with Doctors Without Borders - by accident, because someone cancelled - could have been the beginning of a Mr. Hulot adventure were it not for the ways in which it changed our weary traveler. Something Tati never allowed his alter ego.

The fascination for this former colony of Belgium goes all the way back to the propaganda material the child who would become the painter encountered in his childhood home and testified of an exoticism he would only later came to understand when the discussion about the horrors of our national past was given its rightful place in the public discourse and imagination. A Paradise tainted by blood. With this combined mindset of the child who encounters memorabilia and a certain way of portrayal it didn’t understand and the young man afflicted by the knowledge that contaminates his childhood retroactively, the artist embarked on a journey for which he was not pr pared. Les mots sont pas les choses. Theory is easy when it does not have to adjust itself to a lived experience. What our protagonist encountered was beyond his imagination. The subjects of which all theory so easily talked, turned out to be human beings not necessarily occupied with the themes he came to expect, but with living life in its (entire) complexity. An aha-erlebnis of normalcy. Leaving all his preconceived ideas behind, the painter started looking for images that were not so easily defined or explained in hopes of undermining in his audience the exact same prejudices he had held.

Once back home Lutgens came across the humoural theory, a medicinal system rooted in the origins of Western civilization, that divides people into different categories based on the specific liquid that reigns their physical and mental constitution. From a modern day point of view said theory is as scientific as heliocentrism, but what interested Lutgens was the fact that once this had been the pinnacle of Western science and as such it became his metaphor for the hubris of western imperialism that had always claimed its legitimacy in the shadow of this most treacherous of all gods that goes by the name of science.

A pretense to superiority serving as a pretext for debauchery.

And then, what he believed to have been an emblematic symbol of the past, gained relevance once more when a plague straight out of Il Decameron kept our joyous wanderer locked at home. Theories of the pseudoscientific and conspiratorial kind formed an unholy alliance that made mankind’s delusional claim to s premacy vanish like toilet paper in the supermarket. The timelines were full of gibberish but the streets, for the first time since he moved here, laid empty and so, once more, the seismographic impersonation of our times set out to discover what had been hidden in plain view all along. Even at night when he came home from the newfound strangeness of his surroundings, he learned yet another way of transcribing what had been happening all around him. The graphics and crosses which were the cu rency of the new normal found its counterpoint in the fluctuating hysteria of the stock market. This turned out to be the last sign code he needed to complete his research and finalize the iconographic building blocks of the universe he wanted to paint.

Taking the advice to heart to never waste a good crisis - and if not now, when has there ever been a good one? - our hero, as reluctant as he is enthusiastic, finally stops in his tracks to bring all these disparate influences together in the paintings collected in this exhibition. Using the formalistic conventions of an ironic heritage, he nevertheless attains the expression of something sincere. Like the philosophical idiot who did his utmost best to unlearn all the fallacies he was acquitted with since birth and now only knows he knows nothing, the artist made the world into his own theatre wherein he can stump around like a bull in a china shop with the grace of a prima ballerina. Forcing a pathway to possible exits by presenting us with the alloy of his observations, imagination and scattershot references. Not merely asking questions, which seems to be the hype in contemporary art nowadays,

he is unraveling the framework wherein these questions originate. The image deconstructed by the story of its creation. Alternating between the power and impotence of the theatrical madness at the end of the world as we know it William Ludwig Lutgens presents with his Comedy of Humours the dysfunctional family of man.

William Ludwig Lutgens’ A Comedy of Humours

17.12.2020—17.01.2021 PLUS-ONE Gallery(Antwerp, Vlaamse Kaai 74, ZUID)

By Michaël Van Remoortere

All the world’s a stage and according to William Ludwig Lutgens (1991) the theatre unfolding itself on it

is a comedy. The scenes he brings together in this exhibition express his understanding of the human condition in all its vibrant absurdity. Seemingly banal sequences from the everyday life are enriched with references to the history of art and the debris of modern-day urban life giving the paintings an air of uni- versality while at the same planting them firmly in the contemporary. Bringing back home the experienc- es and influences he gathered during his residency in Korea and as a fellow traveler with Doctors Without Borders in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Lutgens saw his familiar surroundings with new eyes. A discovery that resulted in his most mature works as of yet.

The Content of Matter

Considering himself a draftsman first and foremost, Lutgens had been looking for a carrier that would allow him to draw and paint at the same time and with the same swiftness. When he stumbled upon the Hanji paper that has been used for centuries in the Korean pictorial tradition, it was nothing less than an epiphany. In combination with the direct practice of applying paint unmediated to any available surface, as he had witnessed local painters doing in Congo, he developed a style that allowed him to bring his characteristic figurines, in which the hand of the artist manifests itself most strikingly, into the domain of painting. Maintaining the deliberate flatness of his drawings in the outlining of the dramatis personae of his paintings, allows him to focus more on and play more intensely with the composition of his theatrical tableaux both in terms of scenography and color. The latter consisting mostly of the earthy tones he also brought back from his trip to Congo.

Capprici alle Puttinesca

Using the humoural theory - which claims the human body and soul are regulated by four bodily flu-

ids and dates all the way back to the origins of Western civilization - as the thematic focal point for the histrionic approach of his subject matter, Lutgens populates his parade of stories with the archetypal figure of the putto. These chubby, childlike incarnations of human folly contrast the gravity of the issues addressed in the scenes - some of which are taken from news footage of riots and protests, others were witnessed by the artist himself - with a joyful and almost obscene innocence. History presenting itself

as farcical debauchery with an emphasis on piss and jizz, puke and blood as narrative and compositional motives. Whether they are fighting over a statue, operating or torturing a patient with sausages, engag- ing in sexual ceremonies of the sadomasochistic kind or making a victory lap on the back of a goat, they never fail to unleash and embody mayhem and mischief.

A Belgian Master (of None)

Belgium is a country born out of theater and, as such, has a predilection for it in its DNA. Lutgens is unmistakably a scion of our long tradition of artists engaging with the comical gap between our aspira- tions and reality. In the paintings brought together here we find the scabrous carnality of Breughel and a joyous unmasking of Bourgeois complacency reminiscent of James Ensor. One is also reminded of the etchings of Goya in the way our present is used to show us our failings when filtered through an ironic sensibility that is nevertheless paradoxically used to express something sincere.

As if Lutgens is not only saying “Ecce homo” but also “Isn’t he ridiculous?”

WILLIAM LUDWIG LUTGENS

The rules of the game (and how to bypass them)

April 2020

By Koen Leemans

At the end of 2017, William Ludwig Lutgens (°1991, Turnhout) completed a two-year postgraduate degree at the HISK in Ghent. Prior to that, he earned a Master's degree in Art and Design from the Sint-Lucas School of Arts in Antwerp after already obtaining a Master's degree in Illustration and Graphic Design. After winning several important art prizes, his artistic practice took a promising start. In 2017, he won the Eeckman Art Prize (Bozar, Brussels), The First Line Award-Lyra Prize (Drawing Room, Madrid) and was runner-up in Art Contest (Boghossian Foundation, Brussels). This year, he was laureate of the biennial Gaver Prize for painting.

The work of William Ludwig Lutgens has gained quite some momentum lately. In his eclectic earlier works, he eagerly expresses the urge to try things out in different media, styles and materials. To call his art diverse is in this sense an understatement of epic proportions. To generate maximum impact, the artist sometimes seems to want to cram as much information, stories and ideas into every work. A barely restrained tension is tangible in each of his works. The artist does not shy away from any formal or material experiment. However, he does seem to be gradually refining his work so as to uncover the meaningful essence of what he wants to express, and the way in which he wants to express it. Lutgens, responding to specific narratives and changing contexts, produces paintings, drawings, sculptures, publications and installations. His multi-disciplinary working method and multifaceted process of creation complement each other and give shape to his multifaceted, idiosyncratic artistic practice.

Despite the great formal diversity of his works, frequently recurring themes and motifs form a common thread throughout his oeuvre. Through his artistic practice, the artist creates stories that reflect on cultural diversity, interpersonal relationships, the influence of social and political systems and, more recently, the post-colonial history of the Congo. Using a multitude of stories and relationships, Lutgens creates associative, playful works that always retain a critical undertone. Sharp reflection fuelled by everyday reality leads him to the creation of a colourful and seemingly accessible oeuvre. The works of William Ludwig Lutgens immediately affect the viewer. They are direct, powerful and often funny. Through regular winks at art history and not without irony, the artist succeeds in confronting different things with each other in different ways, not only on a rational level, but also instinctively and intuitively. Often, his art is a reaction to what he sees, experiences or has experienced. He transforms big and small events from his own life and from society into a heterogeneous oeuvre.

With his eye for what at first sight may seem banal, everyday events and anecdotes, he dissects our human behaviour and social fabric. Since 2016, he has been the publisher, designer and editor of Het Geïllustreerd Blad, an irregularly appearing magazine. Like a skilled satirist, he cleverly makes fun of popular media and advertising and delivers a striking, grim commentary on the absurdity of politics and society. Through playful use of platitudes and clichés, William Ludwig Lutgens' art aims to expose problems and raise questions. And preferably more than he himself consciously includes. However, in his view, it is not up to the artist to provide answers or solutions.

A striking example of his socio-critical attitude is the space-filling installation Please play by the rules from 2018, a work he made during his residency at FLACC in Genk. The work consists of five wooden panels, each containing one word from the title. The panels are painted in a flat, almost clumsy manner that is most reminiscent of Walter Swennen's style and especially of the radical and associative way in which he explores the relationship between text, symbols, meaning and pictorial handling. The panels are mounted separately on simple wooden slats and stand upright on ceramic bases. Hands – also in ceramics - are visible on the edges, and seem to be holding the panel. In the work of William Ludwig Lutgens, each panel becomes a character, an actor in a cheerful yet estranging staging with which the artist refers to street demonstrations and the protest signs that are commonly used on such occasions.

The work resembles a peaceful demonstration of sorts, as a sign of positivism and hope. The slogan Please play by the rules invites us in a very polite and friendly manner to respect the rules. Beneath the colourful comic surface, the sharp, critical multivoicedness of the work unmistakably seeps through. By depicting freedom of protest as a seemingly innocent and harmless liberty, Lutgens unambiguously denounces the hypocrisy of those in power who flout their own rules and laws.

A recent artistic voyage to Congo – upon the invitation of Médecins Sans Frontières and Marianne Hoet –, and the unforgettable impressions he gained there, inspired William Ludwig Lutgens to create an ever-growing series of new works. At first glance, the imagery in these works seems to lean towards the colourful, the exotic and the fascinating. There are no direct references to the loaded reality of the colonial system we are all well aware of today. In his paintings and drawings, the artist explores narratives and images which he counterbalances – in his characteristic humorous, playful and ironic manner – with a sense of context, nuance and seriousness.

The critical significance of The Belgian Baggage (and the Guilt Quilt), a work from 2019 from the 'Congo' series, however, leaves nothing lacking in clarity. Lutgens presents us with a soft-looking sculptural installation featuring a well-stocked backpack next to a colourful chequered, half rolled-up blanket on a patchy cardboard surface. It could easily be the harmless belongings of a homeless person or fugitive. As is often the case with William Ludwig Lutgens, nothing is what it seems. The squares on the blanket all appear to contain images of illustrious figures and dark facts from the history of the Belgian Congo. The packed backpack is decorated with sewn-on patches of Tintin, the Smurfs, Simba beer, the Belgian tricolour and Leopold II, as well as painted texts such as 'Stanley Choco', 'Union Minière de Katanga', 'Mistabel' and 'Het Beschavend Belgenland' (The Civilising Land of Belgium). In this way, Belgian Baggage directly appeals to the spectator and forces them to take up a position – or at least call the matter into question. By presenting this installation as a metaphor for Belgium's colonial past, Lutgens explores the boundary between the work's naive, doltish appearance and its caustic, oppressive meaning. Some kind of absurd Reparation ritual, as it were.

The trip to Congo not only provides the artist with a wealth of anecdotes, stories and a certain historical awareness, he also becomes fascinated with materials and techniques he was previously unfamiliar with. Back in the studio, Lutgens starts experimenting with, among other things, works in clay and colour pigments. In his search for new three-dimensional forms, he makes full use of the FLACC workshops where he can set to work with wood, metal and ceramics. The two-year residency allows him to expand his artistic practice in a meaningful way and now includes objects, sculptures and installations.

The lively use of pigments and the non-academic, brutal, almost 'dry' painting technique used by Congolese mural artists inspire William Ludwig Lutgens to create a similar effect in his drawings and paintings. Lutgens describes himself first and foremost as a draughtsman who paints. Drawing is the foundation of each of his works and indeed his entire artistic practice. His fresh approach, hovering somewhere between Willy Linthout and James Ensor and drawing on Congolese inspiration, yields dynamic, nervous graphic compositions.

Although not displeased with his first artistic experiments, the artist feels that the real breakthrough only occurred when he discovered Hanji paper in the homeland of his South Korean girlfriend. Hanji is traditional Korean handmade paper and is produced with the inner bark of the mulberry tree. Out of respect for this centuries-old manual process, Lutgens starts to use the marouflage technique himself, which allows him to work on larger formats as well. The special tactile qualities of the paper make it possible for him to paint faster. By applying less paint, he achieves a more direct result, allowing the characteristic energetic properties that he derived from his African impressions to come to the fore.

Lutgen's choice of suggestive, grotesque scenes, bizarre figures and trivial objects imbues his sculptures with a powerful, evocative ambiguity. His paintings, evincing a richly contrasting and bright use of colour, sometimes painted in an expressive, vibrant style, at other times simple, almost childlike in appearance, acquire a special tensile quality. His paintings quite rightfully penetrate deep into the neural pathways of contemporary Belgian painting.

William Ludwig Lutgens' Theatre of the World

November 2017,

Hisk Catalogue ‘The Grid and the Cloud: How to connect”,

by Pauline Hatzigeorgiou,